Exploring and Understanding: Depression

‘Depression’ has a long history, and has come to be used as a colloquial term in everyday life - a sense of feeling ‘down’, ‘saddened’ or overall ‘melancholic’ about some particular event, circumstance, or chapter in life. The symptoms of depression may help us understand what is meant by this encompassing term - they include sadness, fear, anxiety, despair, an overall sense of helplessness and overwhelm.

In this short piece, we will look to explore how depression may be understood from a developmental frame, whilst briefly outlining some strategies for managing and overcoming depression.

Defining Depression

According to the ICD-11 (International Classification of Diseases), a “depressive disorder” is characterised by “depressive mood (e.g., sad, irritable, empty) or loss of pleasure accompanied by other cognitive, behavioural… symptoms that significantly affect the individual’s ability to function.”

Central to understanding ‘depression’ is the recognition that this is a broad term referring to a condition which arises out of a constellation of symptoms, oftentimes thought to be rooted in causes which lay much deeper than the surface level expression.

From this perspective, we may understand depression to be a state of the nervous system - a ‘depressed’ (flat, de-energised, and potentially shut down or collapsed) expression of our being, manifested as a series of symptoms and states of mind outlined above.

Highlighting and Understanding the potential causes

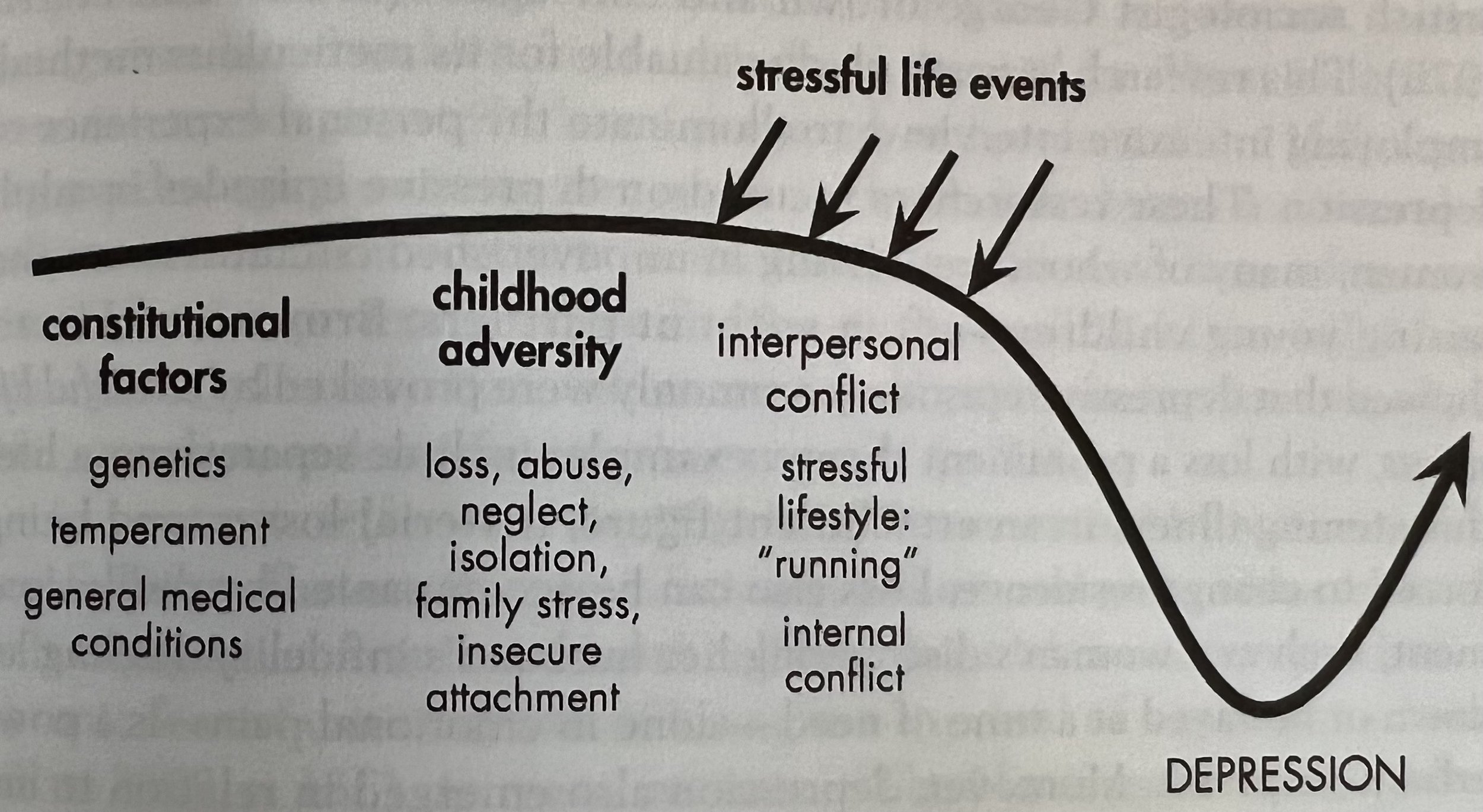

One explanation attempting to shine a light on the cause of depression is what psychiatrist Jon Allen and colleagues refer to as a “stress pileup” (Allen, 2012) - a series of stresses, accumulated over the course of life itself, coming together in a way that overwhelms the system (the nervous system) of an individual.

Of these stresses, interpersonal stress (that is, feeling emotional and psychological distress from relationships) is central. These interpersonal stresses may include; childhood trauma, unstable relationships with caregivers, and in turn never being afforded the opportunity or space to develop the capacities to cope with difficult emotions, and the impact they may have on one’s wellbeing.

As a result of these developmental experiences, it may be difficult to know how to regulate or cope with intense emotional experiences. Relational disturbances or conflict, and other life stresses (such as work, family, or other responsibilities) may overwhelm a system which isn’t equipped to handle the potential intensity of the associated emotional and psychological adversity. As Allen notes, individuals with a history of childhood/attachment trauma experience a significant vulnerability to more recent stress that can trigger a depressive episode in their adult context.

Complementary to Allen’s theory of “stress pile-up” is the work of psychotherapists Walter Joffe and Joseph Sandler, in what they refer to as the “depressive reaction” (1965). They note that this reaction arises as a neurological response of defeat when the environment is unresponsive to efforts to change it. This may lead to helplessness, apathy, and a sense that one is unable to exert any control over the forces which are causing psychological/emotional pain. Repeated painful interpersonal experiences and their associated environments can leave an long lasting imprint on an individual’s sense of capacity to feel like an agent of change in the face of adverse life circumstances. In turn, depressive symptoms may arise in these instances throughout life, originating in earlier life experiences in which one felt helpless and/or hopeless to changing the outcome through action and agency.

It is important to note that there are many factors which contribute to the vulnerability to developing depression. These developmental frames provide us with a brief and partial means to understanding how it is that early life experiences may shape our nervous systems and being-in-the-world, and in turn, impact our functioning later in life and potentially cause this ailment.

Source: Allen, J. G. (2012). Restoring mentalizing in attachment relationships: Treating trauma with plain old therapy. American Psychiatric Pub

Managing and Overcoming Depression

As anyone who experiences (or has experienced) depression would know, taking the practical steps towards alleviating the symptoms is no easy task. Indeed, as Jon Allen (2007) notes, depression is a ‘Catch-22’; the things you need to do in order to overcome depression are the very things which are made difficult by the symptoms you may face.

However in looking to begin this process, a key step in managing and overcoming depression may be understanding how it may have come about. In such an instance, insight and understanding may re-instill a potentially lost sense of empowerment. Beginning to understand the causes of your depression may be the invitation first needed for contextualising your challenges with compassion and curiosity.

Practical steps which may prove helpful in managing depression include:

Developing a small list of easy-to-do self care tasks: Taking a shower, brushing your teeth, going for a walk to the corner and back - each one of these is a milestone to be celebrated, no matter how seemingly insignificant it may be. Exploring small steps which may incrementally shift your mood can be a first step towards shifting the state you may find yourself in.

Physical activity: Daily exercise is a natural means of improving your mood. Physical activity releases endorphins which in turn shift and lift our mood. Some examples of physical activity may include going for a walk, practicing yoga, or playing a group sport (which doubles as a social connection activity).

Developing support systems and networks: Thinking about individuals or networks that may be able to provide you various different types of support can be a game changer for when you’re feeling down. Support can take on many different forms. Some examples include;

Emotional support - This may take the form of someone you know, trust, and feel safe and comfortable with to speak to about what’s going on for you. Friends and family members who offer a shoulder to cry on or lend a sympathetic ear can significantly reduce feelings of isolation and loneliness, which are common in depression.

Practical support - This may include a network to help with daily tasks or responsibilities that may become challenging during depressive episodes. This can include cooking, cleaning, childcare, or running errands. Friends and family can assist by providing meals, helping with chores, or taking care of necessary tasks to reduce the burden on the person experiencing depression.

Professional support - These systems and networks may include mental health professionals, who may be able to support you in exploring what’s going on for you, and ideally will collaboratively develop an understanding and treatment plan, paving a pathway towards hope and a brighter tomorrow.

Important to note is the nature of depression and other mental health conditions both impacting the individual suffering, as well as those in their lives. If you, or someone you may know, is experiencing depression, or is impacted by it in any way (either directly or indirectly), you may consider reaching out for further support.

Are you seeking support through therapy?

We’ll connect you with a therapist aligned with your needs.

Sources

Allen, J. G. (2007). Coping with depression: From catch-22 to hope. American Psychiatric Pub

Allen, J. G. (2012). Restoring mentalizing in attachment relationships: Treating trauma with plain old therapy. American Psychiatric Pub

Joffe, W. G., & Sandler, J. (1965). The Depressive Reaction.

Photo by Nik Shuliahin on Unsplash